In this section, Federico Villalobos interviews colleagues worldwide in the finance and infrastructure industry. The objective of these conversations is to provide readers with first hand experience from experts as well as an update on international best practices.

This week, we talked to Natan Levy. Natan is an independent investment consultant who spent several years in Santiago, Chile, researching Latin American financial and infrastructure markets for BNamericas, where he also set up the company’s Project Risk Analytics unit. Most recently he participated as a contributing analyst for the 2017 Infrascope report by the Economist Intelligence Unit. Previously, Natan spent over a decade managing pension funds and researching investments in the UK. He is based in London, UK.

As an industry expert, Natan Levy analizes the Latin American environment for private infrastructure investments and the main challenges ahead on a global competitive environment.

What have been the main issues for infrastructure provision in Latin America in recent years?

Across Latin America governments have been trying to find a way to improve public services and infrastructure in order to close the so called ‘infrastructure gap’.

Unfortunately, in the case of most countries in the region, their past record at providing a stable and welcoming environment for foreign investors has often been patchy; from Argentina’s past sovereign debt defaults, to coups d'état and expropriations in several countries.

Furthermore, the project selection, execution and the delivery of public services at anything approaching value for money has been woeful, with cost overruns due to defective selection, planning and in large parts due to corruption as in the case of Lava Jato in Brazil. In 2015, my work at BNamericas brought to light the approximate scale of the issue, revealing US$141bn worth of cost overruns, on initial cost estimates of US$367bn for the largest 200 projects in the region. No wonder therefore that the public in Latin America distrust their politicians to deliver the public services they need, as highlighted in the recent IPSOS/MORI Global Trends survey.

“In Latin American project selection, execution and the delivery of public services at anything approaching value for money has been woeful. In 2015, my work at BNamericas brought to light the approximate scale of the issue, revealing US$141bn worth of cost overruns, on initial cost estimates of US$367bn for the largest 200 projects in the region. US$141bn worth of cost overruns, on initial cost estimates of US$367bn for the largest 200 projects in the region. ”

What major trends do you see in the PPP industry in Latin America?

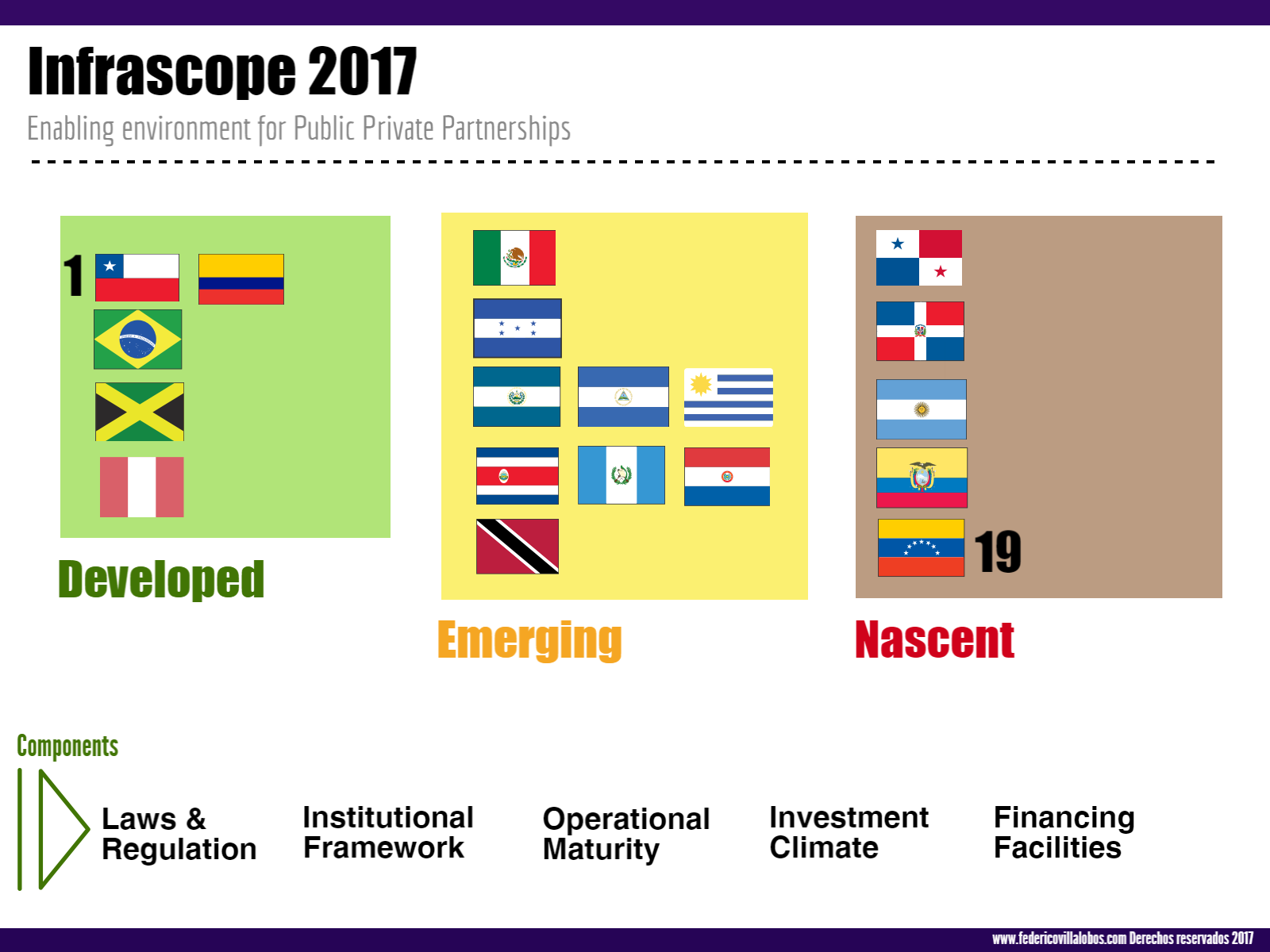

The major trend that is clear from the 2017 Infrascope report, is that the work of the multilateral institutions is beginning to bear fruit, with most countries in the region concentrating heavily on putting in place a legal and regulatory PPP framework based on best practice from across the world; focusing on project selection, contractor selection and monitoring.

Countries in the region now seem to accept that they do not have the resources to solve the infrastructure gap on their own and that in providing a stable environment backed by clear legal and regulatory frameworks, they can facilitate the necessary large investment for long term construction and service provision.

While the private sector itself has not done better at delivering projects on time and on budget according to my research, there is simply not enough money in the public sector to pay for the required infrastructure. The solution must therefore come from a partnership with the private sector, albeit, one that can ensure not just stability but strong monitoring and adherence by both sides to contracts.

Such a partnership should ensure that project selection itself is geared to delivering value for money and not geared towards vanity projects or politically attractive but value destroying mega projects. The ideal scenario would be of smaller, less complicated projects that garner less of the headlines but can be delivered on time and on budget.

Could you please expand on the main findings of Infrascope 2017 on Argentina and Costa Rica?

Both Argentina and Costa Rica implemented a new legal and regulatory framework for PPP project, selection, tendering and monitoring for the first time at the end of 2016, following years of underinvestment in infrastructure.

Both countries have also had little or no experience in PPP project delivery over the years. This will necessitate time and investment in the public sector itself, to ensure that ministries and public bodies are staffed properly with the required expertise to ensure that all stages are carried out in the right manner.

Argentina. In the case of Argentina, the underinvestment followed from its sovereign debt default at the end of 2000 which closed off the country’s capital markets for 16 years, drove away foreign investors and constrained the government’s ability to raise funds.

The new government of Mauricio Macri settled the country’s disputes with bondholders and moved to encourage foreign investors to return to the country. In the case of PPP projects, the government elected to provide an additional legal framework to that which was in place previously, that should allow for a more balanced and predictable cooperation between the private and public sectors, providing legal certainty, in order to attract investment to the country and to the infrastructure sector in particular.

The main challenge for the country lies in restoring investor confidence in order to raise the required financing—both at the federal and provincial levels—after years of underinvestment. Previous studies estimated that US$290bn of investment will be needed by 2024 to finance projects in oil and gas exploration, electricity generation, and highway and rail construction.

To tackle underinvestment, the government aims to launch an ambitious infrastructure program, increasing capital spending from 2% to 6% of GDP in about 8 years, with two-thirds coming from partnerships with the private sector.

Costa Rica. In the case of Costa Rica, there is much similarity, albeit with greater public scepticism of the role of the private sector. This means that politicians should stand up and explain the need for the partnership. The belief that a country can provide for its populace entirely out of taxation has lost ground in Latin America over recent years, but a social system made up of distinct classes continues to engender a lack of trust in the ruling elites and in business owners.

“Costa Rica has shown that it can be a model to the world when it comes to environmental policies and their economic, its politicians must now put as much effort into improving its road system and the rest of its public services to ensure this new PPP framework can succeed.”

In addition, the institutional fragmentation in the country has created a labyrinth of ministries and responsibilities. This new legal and regulatory framework aims to disentangle the relationships, cure the paralysis and ensure clearer reporting lines. Costa Rica has shown that it can be a model to the world when it comes to environmental policies and their economic, its politicians must now put as much effort into improving its road system and the rest of its public services to ensure this new PPP framework can succeed.

What recommendations could you give to Latin American countries to become attractive market for private investment in infrastructure?

While I am not sure I am in a position to advise countries, an important point to remember is that all countries are in competition with each other for foreign investment and must therefore provide a degree of certainty for investors which must include a visible project pipeline.

The stability of institutions, rule of law, property rights and the maintenance of consistent policies are therefore of paramount importance. Those countries that can demonstrate a solid track record will be able to raise funds on a more consistent basis and at a lower cost. Those which fail will only be able to do so sporadically and at a much higher cost.

In my experience, there is also a tendency for countries in the region to compare themselves to each other or to their nearest neighbours or to whoever makes them look better. This is natural but is not particularly ambitious in most cases. The competition is global and it is important for Latin American countries to set the bar higher by benchmarking themselves to the best countries, if they are indeed serious about seeking improvements in their economies.

“The competition is global and it is important for Latin American countries to set the bar higher by benchmarking themselves to the best countries, if they are indeed serious about seeking improvements in their economies.”

Lastly, an improvement in transparency is crucial for creating a well-functioning and competitive system of concessions in order to advance the public debate, engender trust and reduce corruption.